there is little left at all

February 7 - March 28, 2026

Curated by Bella Marinos and Henry Littleworth

Opening Reception February 14, begins at 2:00 PM

Artist Talks begin at 2:30 PM

5613 San Vicente Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90019

Press Release

Hannah Sloan Curatorial & Advisory is pleased to present there is little left at all, a group exhibition curated by Henry Littleworth and Bella Marinos. The show features six artists united in their multidimensional approaches to ritualistic object-making: Littleworth, Marinos, Arianna Patterson, Ika Pearl, Lev Sibilla, and Helena Westra. Part of California’s lineage of assemblage and experimentation with printmaking and ceramics, these works are aggregates of material and memory, composed of clay and cyanotype, found objects and felt. Together, they form an extended altar to ephemeral histories and emotions, honoring death and decay, offering moments for reflection, and hopefully, stimulating renewal.

Helena Westra’s (b. 2000) practice is deeply rooted in local history, natural cycles, and archetypal symbols. Lying Fallow—the golden meadow and accompanying soundscape marking the entrance to the exhibition—began as a response to personal burnout, and seeks respite in nature’s ebbs and flows. In agricultural practices, a fallow field is left unplanted for a season so the soil can regenerate; in naturopathy, the “inner autumn” is an essential but often uncomfortable phase of the menstrual cycle that requires rest. Westra honors seasonality with the communal “planting” of these grasses in hand-mixed adobe, both sourced near her home in San Diego County. To cultivate slowness, she placed a small stool inside the meadow where you can pause, listen, and feel the earth underfoot. Closely linked to this notion of restoration is Now I lay me down to rest: a controlled burn, a multifaceted performance and sculptural piece invoking the regenerative power of fire. In 2022, Westra buried and burned the ceramic skeleton—made to her exact proportions, and composed of individual sculptures of Southern California flora and fauna—in a pit fire; the skeleton now rests peacefully in savasana, or corpse pose. Though the American government has intermittently banned controlled burns, Indigenous communities in California have used this practice for centuries. Integral to forest stewardship and land management, burns like these offer a way for humans to aid and protect the ecosystems they inhabit.

Focused on intimate histories, generational loss, and archiving techniques, Los Angeles artist Henry Littleworth (b. 2001) turns the discarded and the overlooked into objects marking time, place, and process. On view is a selection of works from small bones of the valley, a series of thirty photographic collages combining images of Los Angeles and scavenged ephemera to create a kind of exquisite corpse. Littleworth warps his film photos during development, applying heat, friction, and force to make root-like contact marks, then peels the film apart and inserts printed matter and celluloid negatives sourced from local fleas and streets. The results are individual pieces of an amorphous portrait, like bones in a body. Littleworth’s wall sculpture, whisper softly, I don’t want entry, is also concerned with this relationship between part and whole, individual and family. Growing up watching his father build and his mother sew, Littleworth treats making as hereditary, and material choices as memorial and recycling processes. The reclaimed wood frame echoes the architectural bracing of the pre-Depression-era carriage house Littleworth’s grandfather inhabited until his death a few years ago. On this foundation Littleworth adds canvas from one of his mother’s projects, ensuring nothing goes to waste.

Raised in California by Mexican and Greek immigrants, Bella Marinos (b. 2000) combines cultural imagery and ritualistic elements influenced by their heritage in ongoing explorations of religion, grief, and identity conflicts. Personal and collective rituals converge in chicken legs, a chimeric sculpture sitting on the floor of the gallery like a fallen god offering prayers, protection, and cleansing. In brujeria—Mexican folk witchcraft—the symbol of the chicken is rich with meaning: black hens in particular are used to clear curses and bad energy, and chicken feet are talismans warding off jinxes. Ceramic hands hang from the sides of the sculpture as symbols of prayer and unity, while the white candles burning around the base are pleas for purity. These many hands and little fires are nods to the ongoingness of religious practice, and to a repetitive fervor that borders on the obsessive. Each hand is marked with three dots: three is one of Marinos’s ruminative numbers, as well as a symbol of the divine trinity.

L.A.-based Arianna Patterson (b. 2002) explores grief, relationships, and myth, particularly that of the witch. Working in a feminist lineage, Patterson uses cyanotype—first popularized by 19th century English botanist Anna Atkins—to record the object histories of her maternal line, which has been fractured by illness and instability. Descrescendo is an ode to Patterson’s mother, a piano prodigy, who both delighted in playing and resented the pressures she faced to practice and perform. In prelude II, a self-portrait, Patterson is draped in a piece of jewelry she found at her grandmother’s house on the day her grandmother passed away from the degenerative effects of dementia. The luminous beads sewn onto all three pieces in the exhibition represent a glittering galaxy of familial connections, as well as the countless objects we leave for landfills when we die.

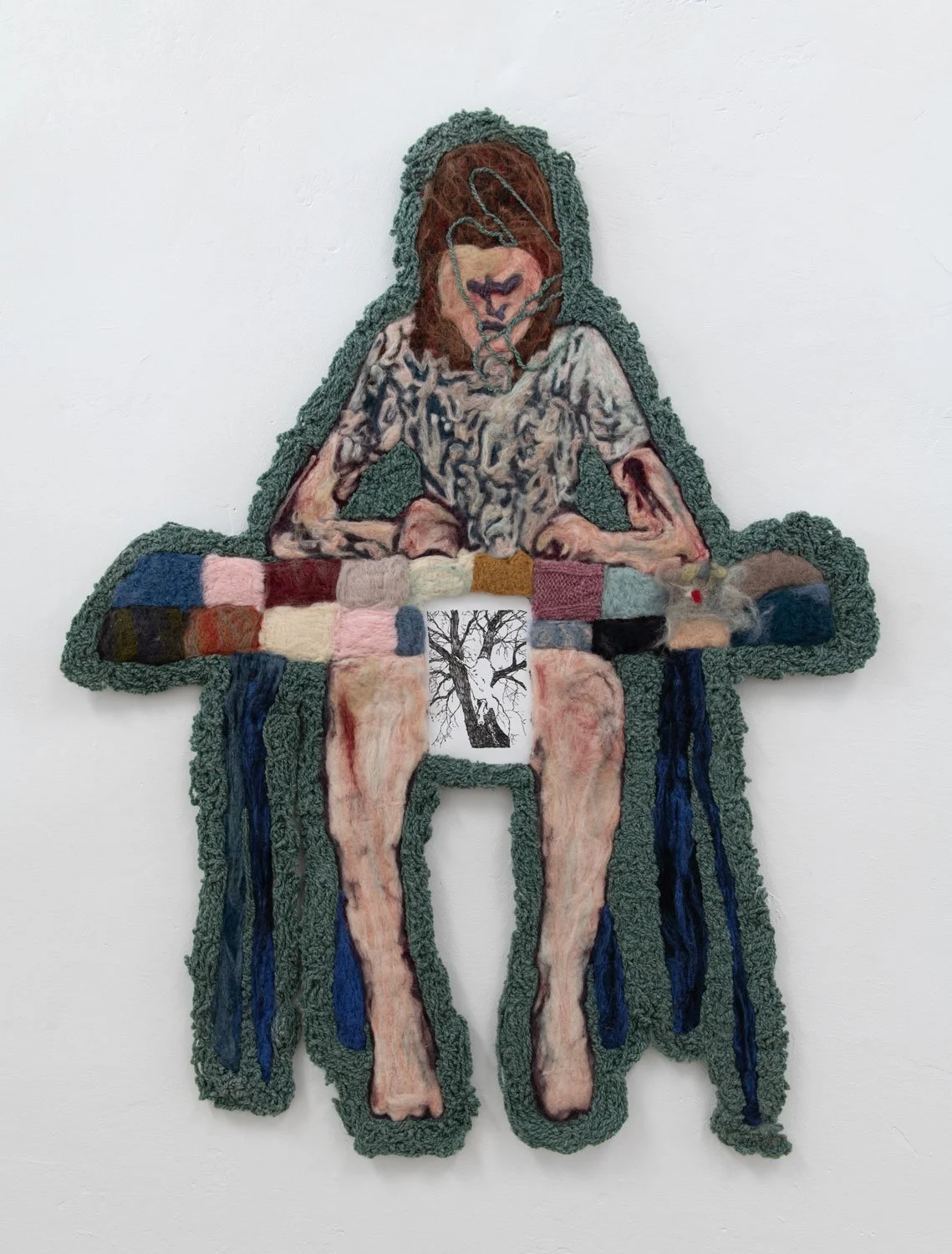

Ika Pearl (b. 2000) is a Las Vegas artist using texture, form, and gesture to create hand-felted wall pieces that encapsulate shifting emotional states and memory-mediated experiences. 2 for sorrow 3 for joy is an amalgamation of hyperspecific memories and feelings: in the same breath, Pearl recalls finding a dead hummingbird, getting bitten by a dog, long car rides and letter-writing. The very nature of this kind of associative logic is reflected in the swirling tufts of the material—the texture of the felt looks something like brain tissue, shaped by a myriad of experiences both good and bad. The image of two hands holding a dead and crumpled hummingbird forms a frame for this piece, and in the blank space between the wrists, there is a small drawing—perhaps the beginning of another story.

Lev Sibilla (b. 1999) is a multimedia artist and professional scavenger in Oregon who turns his found materials into three-dimensional diary entries, ornaments, and tableaus. The products of gradual collecting and sporadic building, his assemblage sculptures—made by hand-sculpting, sewing, and fusing found materials—serve as artifacts of the present moment, or encapsulations of fleeting feelings and worries. They are rife with contradiction, both trash and treasure, human and not. A fur stole is stitched with ribbons of synthetic hair, suggesting a grotesque vanity. A shoulder pad becomes a circus tent, entertainments dangling underneath.

Text by Aleina Grace Edwards

Press inquiries can be directed to Diana Fitzgibbon at diana@hannahsloan.com.